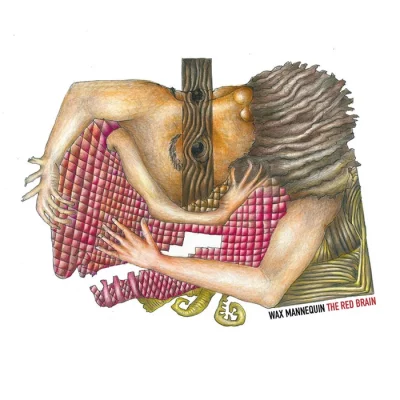

Musician Wax Mannequin (Chris Adeney), from Hamilton, Ontario, discusses his approach to creating music and delves into the concept of neurodiversity and the discovery of his own neurodivergence. He speaks of embracing his idiosyncrasies and creating without conforming to social norms, expressing the value of being open about both challenges and strengths. Chris advocates for a world that accommodates individual uniqueness and neurodiversity, specifically by reevaluating complex social rituals and norms. We conclude with insights highlighting the transformative power of small positive changes in one’s life. Read on for a candid look into the artist’s journey, emphasizing the growth that comes from embracing one’s true self and navigating life’s challenges with a “strange brain”.

STEPH: Who are you and what do you do?

CHRIS: I go by the name Wax Mannequin when I play the music and my real name is Chris. The music I play is my own. Sometimes it’s very catchy pop music with a psychological or absurdist bent, and other times the music is more proggy, more abstract, more upsetting. I like to do both things. To please and make pleasurable music, and make upsetting music. And I like to place pleasurable and upsetting things side by side. I like to present a range of human experience in any record that I produce or any performance that I put on, and over time I’ve come to realize that it’s like a bit of a microcosm of what life is like. Life is not one tone, one style, one psychological perspective. It’s a range of these things that is woven together into a narrative. We weave our lives together into our own narratives. And I try to provide that opportunity with the work that I do.

SP: You are working on a concept album on neurodiversity. I have a definition here: Neurodivergent, sometimes abbreviated as ND, means having a brain that functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of “normal.” Would you consider yourself neurodivergent?

CHRIS: Yeah I’ve come to accept that descriptor a number of years ago. I accepted a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder. All my life I’ve figured something was up and I went through various labels – dyslexic and gifted with attentional problems, deficits here and there, and gifts here and there. Peaks and valleys all over the place. This is the first time I’ve entered the process of album making with a concept in mind. I’ve gone into writing a series of songs revolving not so loosely around the theme of neurodiversity and my experiences of having a strange brain, as well as the experiences of students and other musicians I’ve worked with.

STEPH: I feel like people often fear being themselves and expressing who they really are, especially if they have a unique personality type, are neurodivergent or even just introverted. They feel scared that people might think they’re weird and won’t accept them. It doesn’t seem like you have an issue putting yourself out there, but I’m curious if you’ve ever held yourself back to fit in?

CHRIS: I’ve never shied away from the idiosyncrasies of my work or my instinct. I’ve always created the things I felt like creating, and intentionally with little consideration to what social ramifications might come… to a fault at times. But I think in the big picture I’m really glad that my work has such a range of perspectives, so I don’t regret being weird. I think it’s taken this long for me to really talk about the challenges I face with having a unique mind and trying to interface socially and economically with the world and the challenges that I’ve had all along. I think being open about that, or at least open about it to myself, and now in my work has made it easier. Paradoxically, I always thought it would potentially be too revealing, but I’ve always been too revealing, so I don’t know what I was afraid of.

STEPH: So can you be too revealing? What is too revealing?

CHRIS: I don’t know…. You have certain hang ups or things you don’t want to admit to yourself maybe? As a person, as an artist.

STEPH: Admit to yourself, or to the world? Both?

CHRIS: I think there are certain cards that one wants to keep close to one’s chest in order to feel like you have some semblance of control over your image… or how you communicate. But, you know, I’m not an image counselor. I’m not a publicist. I’ve never had an “image person”. So I’ve always just muddled by, and I think the best way for me to move forward is to talk about these challenges and strengths and to weave them into the fabric of whatever ugly tapestry I’m building.

STEPH: Not ugly!

CHRIS: I’ve got some clashing colors in there.

STEPH: Maybe a few clashing colors! (laughs) So what have been some of your biggest challenges? Even just being a musician.

CHRIS: Keeping my stuff organized, literally my physical objects….

STEPH: I just saw a tent peg fall out of your pants? I don’t know what that’s about! (more laughs)

CHRIS: Yeah, there’s that, and a Crayola marker. I don’t know how it ends up in my pockets. These things just come along for the ride and then I lose them along the way! But when I’m doing something like teaching, I’m able to be a lot more organized because there’s a different mindset. I’ve come to build a ritual around my shows, my performances and my classrooms. There’s sort of a place for everything there, when I’m fully in control of my world – otherwise there would be deficits. When I have to share my world too much, then it’s a lot more difficult for me to keep things in their place, you know? Then the garage gets messy and I lose all the forks or whatever.

STEPH: If you could change one thing about the world or society to accommodate your weirdness or uniqueness – as opposed to changing yourself to fit in – what would that be?

CHRIS: I guess flexible timelines… and a real careful analysis of traditions and you know, what we think of as etiquette. Sometimes very complex, irrational rituals – which can be cognitively taxing activities for many people.

STEPH: When you speak of rituals, can you be specific?

CHRIS: Where you put your knives on the table, how you fold your clothes, the gestures you use when interacting socially… the kinds of eye contact or facial expressions that are appropriate in given situations. Things that perhaps, maybe the word is neurotypical, but a lot of people don’t have to think about. They come second nature somehow. For other people, they take a lot of cognitive resources and fundamentally… I really struggle to see the social value in these things… in you know, the little rituals and routines. Some of them are very helpful, like washing your hands or not putting raw meat on top of your vegetables in the fridge – that makes sense. But other things just get passed down through the generations and lose their context… lose their meaning. They just become the way things are done without any explanation, and sometimes the way things are done is very taxing. It takes a lot of cognitive energy when you’re really trying to think about why things are done that way and carve room in one’s brain for more important concerns. So maybe that’s what I would change about the world, just that social niceties are thought through a little more carefully.

STEPH: Ok, last question. If you could give one piece of advice to someone who is starting out on their creative journey and maybe they’re neurodivergent, or unique in their own way, what would you say?

CHRIS: A creative person?

STEPH: Yeah.

CHRIS: Oh boy!

STEPH: Maybe they want to get into music or something where they’re expressing themselves.

CHRIS: I don’t know how anyone gets into music now or stays in music. I think you have to start channels on all these little surveillance systems.

STEPH: You do! (Laughs) Ok, what if you could go back in time to a young Wax Mannequin and tell him, “Make sure you do this!” or “That was terrible, don’t do that!” Is there anything that stands out that you would do differently?

CHRIS: I would make more little movies and tour a little bit less. Maybe that’s it. I really enjoy touring though, that’s the problem. I just did what I enjoyed, which I think I’ll probably still do when possible. But I always thought it would be fun to make little movies. And it’s ok not to party. I think that’s the big one. It took many years of self loathing to get to a point where I was partying a lot, and because I didn’t like the idea of self destruction, it was very equally challenging to stop doing that. I wonder what trajectory things would have taken if I hadn’t partied so much? It might not have been qualitatively different, but it would have been a different journey. Maybe one that I could remember more?

STEPH: Probably!

CHRIS: I do feel like across the board, there have been many very small improvements in the way my brain and body works. But the cumulative effects are very dramatic. The small improvements across the board can work in tandem to make one’s quality of life dramatically better.

STEPH: That’s good advice. I get overwhelmed very easily – I’m like an anxiety ball. To help combat that, people have suggested I take baby steps. Just do a little bit at a time, consistently and eventually you’ll get there.

CHRIS: Yeah, I think there’s something to that. I’ve found when I stopped drinking, it became easier to do a little jog every night or lift some weights. And then it became a little bit easier to eat well. I try to make subtle improvements once every month or so and see if they stick. I was shocked at how much after the initial, what you would call mourning… I really was in mourning when I quit drinking… it was like I lost a limb – but it was a charismatic, sociopathic limb… a murderous limb that was very charming. And I wasn’t drinking every day, I wasn’t a lush. But I did have to consciously choose when and when not to drink. Like ok, “I’ll drink only on the weekends” or “I’ll do this… I’ll do that”. Not to mention as one gets older, the residual effects of intoxication were really debilitating for a number of days after… a number of weeks after. And as the months go by I feel like new faculties are opening up, because there really is a neurogenesis that goes on. There’s a lot of one’s body that grows back after 20 years of fairly hard drinking in the grand scheme of things relative to, you know, what doctors say is moderate. Recovery is a worthwhile word in that context, because one does recover some things that I didn’t know I was missing.

STEPH: What did you recover?

CHRIS: A little bit of executive functioning, a little bit of remembering names. A little bit of knowing where I put my Crayola marker… a little bit of knowing that I have to not run the red light… and a little bit of not being an asshole. Just tiny incremental things across the board. And those things add up.